What I learned in my first year as a VC

How to avoid the phallus of mediocrity.

Join the 1200+ founders, investors and operators who get these essays first.

First, a disclaimer.

When I first started investing, I had a pretty simplistic view of what it would take to be successful: invest in good companies, and the rest would more or less take care of itself. I quickly realized that the reality was more complicated than that.

I’m not sure if there is such a thing as objective truth in early stage investing, and it’s going to take years before we find out if I’m smart or completely full of shit.

These are just some observations I’ve made after a year in venture capital, thinking about the market, and talking to people who are smarter than me as I attempt to overcome my impostor syndrome.

Finally, it’s important to note that we are a $10M seed fund, which means we are playing a fundamentally different game than high AUM behemoths like a16z and Lightspeed. There are things we can do that they can’t, and vice versa.

That said, let’s press on and share a few observations that seem true to me, at least for now, and that I expect to guide my investing in the year to come.

Hunt dragons before unicorns

One of the benefits of being a smaller fund is that we don’t need unicorns to provide excellent returns. Especially if we can achieve outsized ownership relative to our fund size through concentration and price discipline, we should hunt dragons.

Quick recap of definitions:

Unicorn: A company that achieves a valuation of $1B or higher.

Dragon: A company that returns a VC’s entire fund at exit.

Don’t get me wrong - I have no aversion to the startups I invest in becoming multi-billion dollar companies. But I think we are more likely to get the best returns by chasing dragons. Here’s why.

Keen observers will notice an important difference between these definitions: one is concerned only with valuation, while the other measures returns.

Here are a couple of problems with chasing unicorns:

Valuations are temporary: if the past couple of years taught us anything, it’s that valuations alone don’t tell you much. Perhaps the most memorable recent example of this is the scooter company Bird (peak valuation: $2.5B), whose current market cap of $7M is $15M less than the $21M its founder paid for his mansion in 2021.

Entry price matters: Any idiot can buy into a unicorn, and many did in the past few years. What matters is when you did so, and at what price. Instacart’s recent IPO provides a vivid illustration of this.

Early investors did great, Series C-F investors underperformed the S&P, and everyone else lost money.

Source: The Information, “Why the Two Biggest Winners in Instacart’s IPO Clashed”(9/13/23)

Enter the dragon

Because a dragon is defined by its return profile, it focuses us on what matters - returning money to investors - and gives us some levers we can control, namely the amount we invest, and the price we pay.

The great thing about dragons is that the smaller your fund, the easier they are to find.

We write checks of up to $500K out of a $10M fund, $8M of which is investable capital.1 If we invest $500K in a startup at a $10M post-money valuation and that company exits for $200M or more, it’s a fire-breathing, fund-returning dragon.2

Making an investment like this is by no means easy, but there are a lot more $200M exits than unicorn outcomes.

This also illustrates the benefits of concentration - $500K is a large check for a fund of our size, but investing $250K on the same terms would require a $400M exit to return the fund.

If you are a $1B+ mega fund, the math gets much harder. You have so much more capital to deploy that you need huge exits to move the needle: multiple unicorns, and preferably a decacorn or two. This is a heavy lift, especially in an environment of higher interest rates and multiple compression. The challenge is particularly acute in the games industry, which suffers from a paucity of IPOs and a relatively narrow set of acquirers.

I am fascinated by firms that regularly do identify and invest in unicorns and decacorns, but still keep their fund sizes relatively small. It’s clear that Benchmark has had many opportunities to raise vast amounts of money, but almost every fund they have raised has remained around $500M. As a result, their returns are consistently stellar.

Concentration beats diversification

Speaking of concentration: if you believe you have a better than average ability to identify and invest in exceptional companies, you should pursue a concentrated rather than a highly diversified portfolio construction strategy.

Although roughly 100% of VCs probably believe they are above average pickers, a highly diversified approach to portfolio construction was nonetheless the most common structure for most pre-seed/seed funds during the past cycle.

This made sense to a certain type of investor when everything was going up and to the right. If every company you invest in raises a follow on round and gives you a markup within 6-12 months, why not do as many deals as possible? I know one Web3 fund that was making 3-4 investments per week at the height of the bubble!

Leaving these extreme examples of exuberance to one side, the problem with an overly diversified approach is that it can dilute your returns and leave you insufficiently exposed to the exceptional companies.

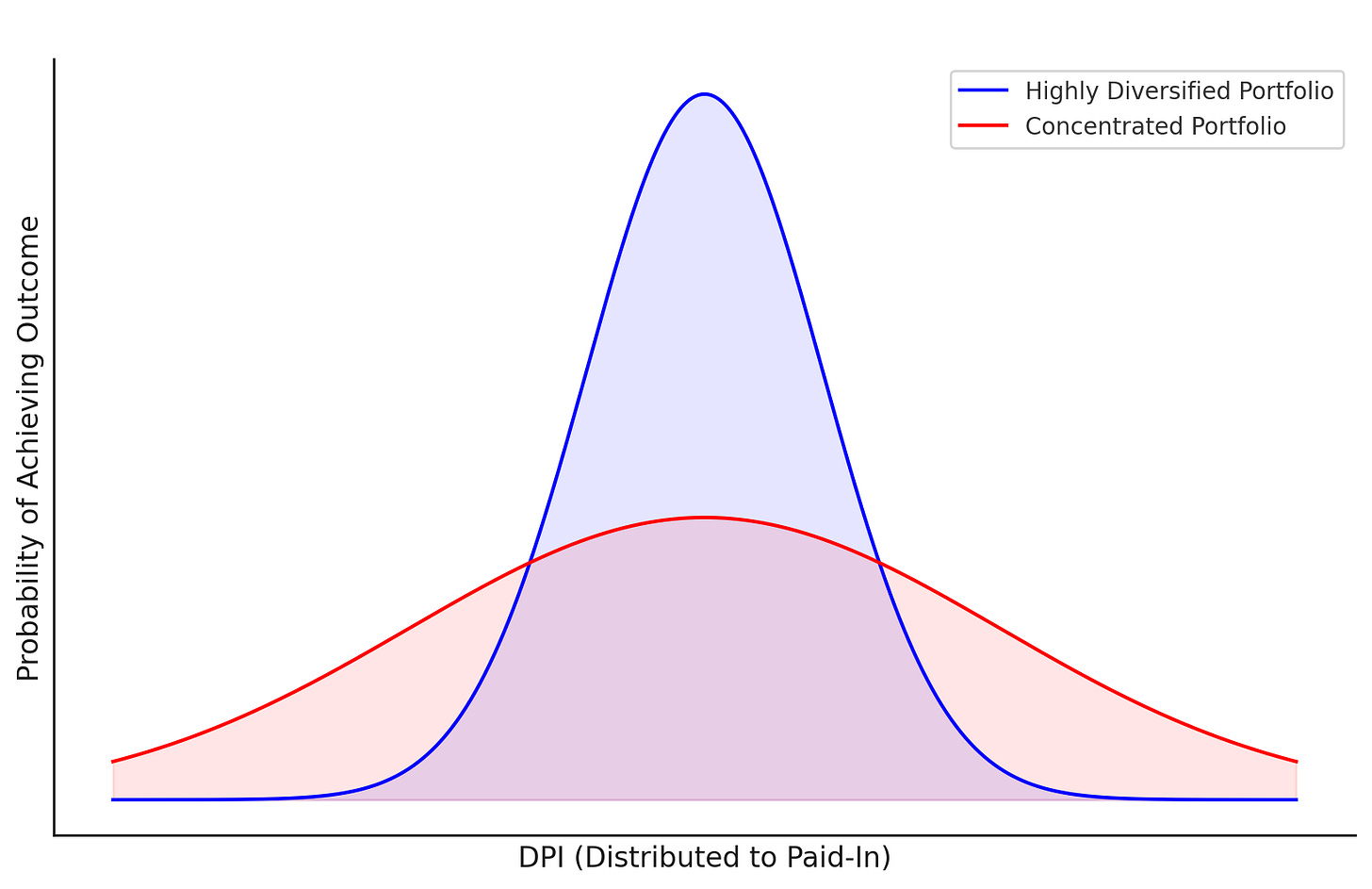

This completely unscientific graph illustrates the point: the more diversified your portfolio, the more likely you are to cut off the extreme tails of performance.

Diversification diminishes your chances of completely failing to return capital, but it also dilutes the impact of your winners. If you are too diversified, you are more or less guaranteed to max out at mediocre returns.

Excessive diversification may not actually be a problem for some LPs. If your anchor LPs are strategic investors whose main reason for supporting you is to gain early exposure to startups they might want to invest in or acquire when the company is more mature, a large portfolio is a benefit that probably outweighs any drag on returns.

But the best investors I have met and spoken with over the past year all shared the following characteristics: they were highly selective, independent-minded and not afraid to bet big on the rare occasions they identified a truly exceptional founder and company. All of them pursued concentrated strategies, and none of them were logo-hunting hypebeasts.

So: if you care only about delivering the best returns and you truly believe you are good at your job, you should put your money where your mouth is and trade higher tail risk for a shot at greatness.

Thanks to Mitch Lasky, Niko Bonatsos, Jeremy Liew and Joakim Achrén for providing feedback on drafts of this essay.

Fear not, venture nerds: we intend to recycle until fully invested.

In the interest of keeping the math simple, I’m ignoring dilution from subsequent rounds.

Invest in my game, Worldseekers, and I can guarantee we can add a dragon. Heck, we can even add a unicorn if fortune allows.