The 7 Paths to Power in Games

Moments of flux and how startups can take advantage of them.

Join the 1900+ founders, operators and investors who get these essays first.

I have often said that 99% of game companies should not raise from venture capitalists. This essay is about what investors look for from the 1% that should.

VCs look for startups that can return huge multiples on their original investment and ultimately exit for hundreds of millions, or billions of dollars. Firms differ in their expectations - fund size and investment stage play a big role here - but at F4 Fund, we ask ourselves this: “If things go really well, could this company return the fund?”

The more capital a fund has to deploy, the bigger those exits need to be. Careers and reputations are made on being early into 9 or 10-figure outcomes like Supercell, Riot Games, Roblox and Zynga.

The reason that most businesses never achieve these lofty outcomes is competition.

Aren’t businesses supposed to compete with each other? Perhaps, but if you want to create a truly valuable company, it is much better to escape competition. Why?

The more competition that exists in a market, the likelier it becomes that profits will be driven down towards zero, limiting the ability of a company to build enterprise value. This is why, as Peter Thiel memorably puts it, competition is for losers:

Since no firm has any market power, they must all sell at whatever price the market determines. If there is money to be made, new firms will enter the market, increase supply, drive prices down and thereby eliminate the profits that attracted them in the first place.

The opposite of perfect competition is monopoly. Whereas a competitive firm must sell at the market price, a monopoly owns its market, so it can set its own prices. Since it has no competition, it produces at the quantity and price combination that maximizes its profits.1

The best way to escape competition is through the acquisition of Power.

I capitalize the word here to refer to Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers, which should be required reading for any aspiring startup founder.

Getting to Power

Before we get to the 7 Powers, it’s worth spending a few moments to think about the conditions under which Power can be built.

Power starts with invention. Helmer puts it well:

The first cause of every Power type is invention, be it the invention of a product, process, business model or brand. The adage “‘Me too’ won’t do” guides the creation of Power.

Action, creation, risk—these lie at the root of invention. Business value does not start with bloodless analytics. Passion, monomania and domain mastery fuel invention and so are central.

When is it most likely that Power can be formed? Helmer has a guide:

Flux in external conditions creates new threats and opportunities.

For a single company, these tectonic shifts do not occur frequently, but you can be certain they are coming. The relentless forward march of technology assures this.

Amidst this cacophony, you must find a route to Power.2

Moments of flux

The history of the games industry is full of moments of flux: windows of opportunity that allowed existing companies to transform themselves, or entirely new companies to be built.

This is what’s behind the “Why now?” question many investors will ask when you pitch. They want to know if you have identified a change in external conditions that has opened a window of opportunity for you to take advantage of.

Great founders are adept at recognizing these moments, and figuring out inventive ways to capitalize on them.

Here are a few major examples from the history of the games business:

In moments of flux, the factors that have allowed incumbents to grow dominant are destabilized, creating opportunity for disruptive new entrants to create their own Power.

What is Power?

A Power consists of two things - a benefit and a barrier.

Each Power creates a benefit for the winning company, and a barrier that prevents its competitors from using it.

Benefit: the way in which the power improves cash flows, such as through lower costs or ability to charge higher prices. This determines the magnitude of power.

Barrier: the way that competitors are prevented from arbitraging the benefit of the power. This determines the duration and durability of the power.

Benefits are common, but barriers are rare. A quick hypothetical to illustrate why:

Super Duper Mobile Games Inc. finds a clever way to use TikTok influencers to allow them to acquire high quality users at a low cost for their new game, Match Merge Mega Mansion Saga.

This creates a benefit that improves cash flows by reducing marketing costs, but it is not Power.

Why not? Within a short period of time, Ultra Mobile Games Inc., Hyper Mobile Games LLC and countless other competitors will observe this user acquisition strategy and copy it, arbitraging away the benefit until it no longer exists. The absence of a barrier allowed competitors to adopt the same benefit, thereby nullifying it.

Powers in the games industry

The 7 Powers are:

Scale Economies

Network Economies

Counter-Positioning

Switching Costs

Branding

Cornered Resource

Process Power

Not all of these Powers are accessible to startups - your ability to make use of them depends on your company’s stage of development:

In this essay, we’re only going to concern ourselves with the Origination stage powers, since these are the ones most immediately relevant to startups.

Startups have few advantages relative to much larger and better resourced competitors. The two origination powers turn these seeming disadvantages into strengths.

Counter-Positioning

New companies have nothing to lose. Big companies have pre-existing businesses with revenues they are reluctant to disrupt in pursuit of an unproven or nascent opportunity. This makes them vulnerable to counter-positioning.

Definition: A newcomer adopts a new, superior business model that the incumbent cannot or will not copy due to anticipated damage to their existing business.

Benefit: Lower costs and/or higher revenues due to a superior product or business model.

Barrier: Incumbents have existing assets and models that they are reluctant to cannibalize, preventing them from adopting the superior model.

An easy to grok example of counter-positioning comes from the early days of Netflix, whose subscription-based DVD rental model marketed under the moniker “No Late Fees” was a direct attack on Blockbuster.

Consumers greatly preferred this model, but for Blockbuster late fees were a substantial source of high margin revenue - in the year 2000 alone, they accounted for a massive $800M or 16% of all revenue. The company eventually reversed course on late fees, but by then Netflix was already on the path to victory.

Cornered Resource

Definition: Preferential access, at attractive terms, to an asset that can independently increase value.

Benefit: Ability to charge higher prices or reduce costs, due to access to the cornered resource.

Barrier: Most commonly derived from the law - e.g. patents, copyrights, and trademarks, but not exclusively.

In games, this might be the rights to a valuable IP, exclusive relationships with influencers who have large audiences, or a proprietary technology that allows you to do something others can’t (these are rare, in my experience).

Case study: The birth of Steam

The launch of Steam is a great example of both of these powers in action.

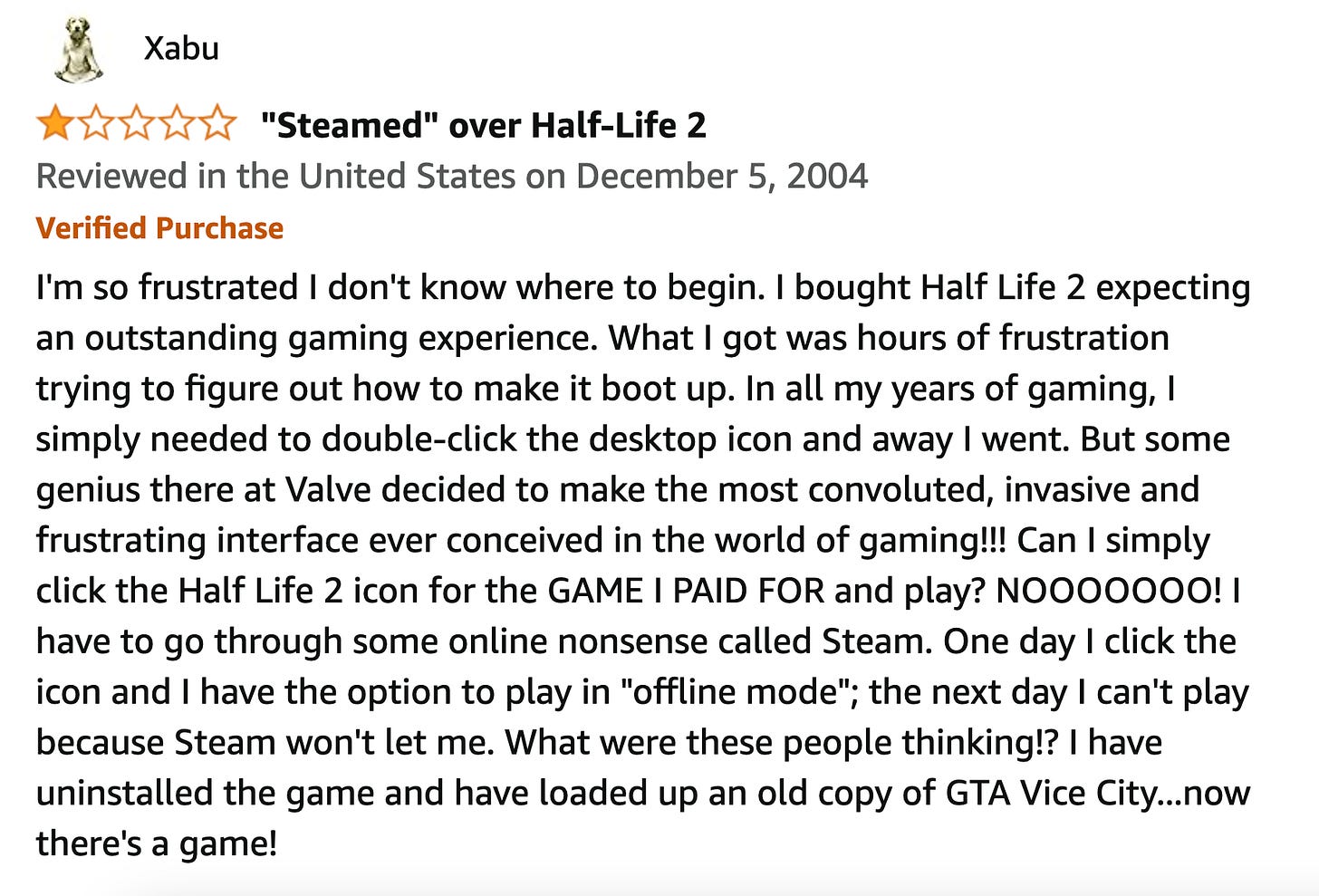

After the success of Half-Life, Valve was a highly regarded developer in charge of a valuable franchise, but far from the behemoth we know today.

The Half-Life IP perfectly fits the criteria for a cornered resource, the ownership of which gave Valve two key points of leverage:

They were able to demand that their retail publisher, Vivendi Universal Games, bundled Steam with every retail copy of Half-Life 2, which gave them an instant install base that would have taken a lot of time and money to build independently.

Consumers wanted to play Half-Life 2 so much that they were willing to install Steam, which in 2004 was a widely disliked piece of software, in order to play it:

Still, as valuable as Half-Life was, there were other publishers at the time with big IPs. Why didn’t they embrace digital distribution as aggressively as Valve?

The best explanation is that Valve’s launch of Steam was counter-positioned to established publishers like EA, Take Two and Ubisoft, whose investment in and commitment to the retail channel made them reluctant to embrace digital distribution.

Like Blockbuster, these companies would eventually reverse course and launch services of their own, but by that point Steam was well into the Takeoff phase and able to use network effects and switching costs to defend its position.

Counter-Positioning in Games

Here are some strategies that have worked recently. Your job as a founder is to re-imagine these for the unique circumstances that exist today.

Subvert an existing IP

It’s plausible to argue that the creation of Palworld is a form of counter-positioning on the part of its developer. They’re deliberately exploiting the popularity of the Pokémon IP and doing things with it that The Pokémon Company and Nintendo cannot and will not do.

You could also say that the Palworld IP, which is now synonymous with the idea of “Pokémon with guns”, has now become a cornered resource for Pocket Pair.

Embrace new platforms

Incumbents are often reluctant and/or ill-equipped to pursue new platforms because they are heavily incentivized to focus their investment on the existing platforms where they are already dominant.

Especially at larger companies, institutional structures and processes are set up to optimize the hell out of existing platforms, making the new platform both difficult and uneconomical to pursue relative to focusing on the core platforms where the company is strongest.

Individual incentives such as compensation and social capital may also discourage the most ambitious and competent people at the company from exploring emergent areas where the upside is still unproven.

Give a premium product away for free

This is one of the best known counter-positioning strategies available to game developers. The history of games is littered with examples of premium games that were disrupted by a new entrant offering a near-equivalent experience for free.

The most successful of these is, of course, Fortnite Battle Royale, which originated as a free-to-play fast follow of the premium title PlayerUnknown's Battlegrounds. It’s also a great example of the importance of timing - the window of opportunity for a fast-follow of an emergent but highly popular play pattern is narrow, and has gotten narrower still since Fortnite.

Reduce friction and cut scope

One way to think about Helldivers II is as a counter-positioned response to dominant live services games that are weighed down by the production and revenue expectations of the AAA titles it competes with.

Arrowhead did not try to compete with games like Destiny on an even playing field - certainly not across dimensions like volume of content, environmental variety, game modes or storytelling.

In doing so, they gained two key advantages - lower production costs, and through clever design, a more accessible and frictionless gameplay experience.

Conclusion

If you want to build a venture-scale game company:

Ask yourself:

What is going to change in technology, culture, demographics and consumer preferences, and what moments of flux those might lead to?

What is happening in the background that makes your success at this very moment inevitable in hindsight?

Why are you the very best team in the world to capitalize on this exceptional timing?

Invent new playbooks. Everything we take for granted today was at one point unconventional. Think about what you can do differently across design, production, distribution and business model that could become a source of Power.

Look ahead. The startup stage is just the beginning. Think about where your business will be if your initial plan works - what future Powers will you be able to leverage?

None of this matters without stellar execution, but a strategy framework like 7 Powers is a valuable roadmap if you want to build a generational company. Are you? If so, get in touch.

Thanks to Joakim Achrén, Mitch Lasky, Niko Bonatsos, Simon Carless and Ryan Rigney for reading drafts of this essay.

“Competition is for losers”, Peter Thiel, Wall Street Journal

7 Powers: The Foundations of Business Strategy (pp. 181-182), Hamilton Helmer

I was literally re-listening to this book again driving back from GamesBeat Next and it still is so useful. Love to see that you're trying to bring this to the game industry.

Good summary. Important that you get this quality of thinking from your prospective founders.