Three Paths Through The Dread Matrix

An investor’s guide to building AI products that actually matter.

My last essay on the agentic dread matrix seemed to resonate with people, which I’ll take as validation that I’m not the only one wrestling with existential questions while checking my inbox for robot-generated meeting requests.

But as I’ve talked to founders over the past few weeks, I’ve realized the matrix isn’t just a framework for processing your feelings about AI. It’s also a useful guide for thinking about building and investing in AI products.

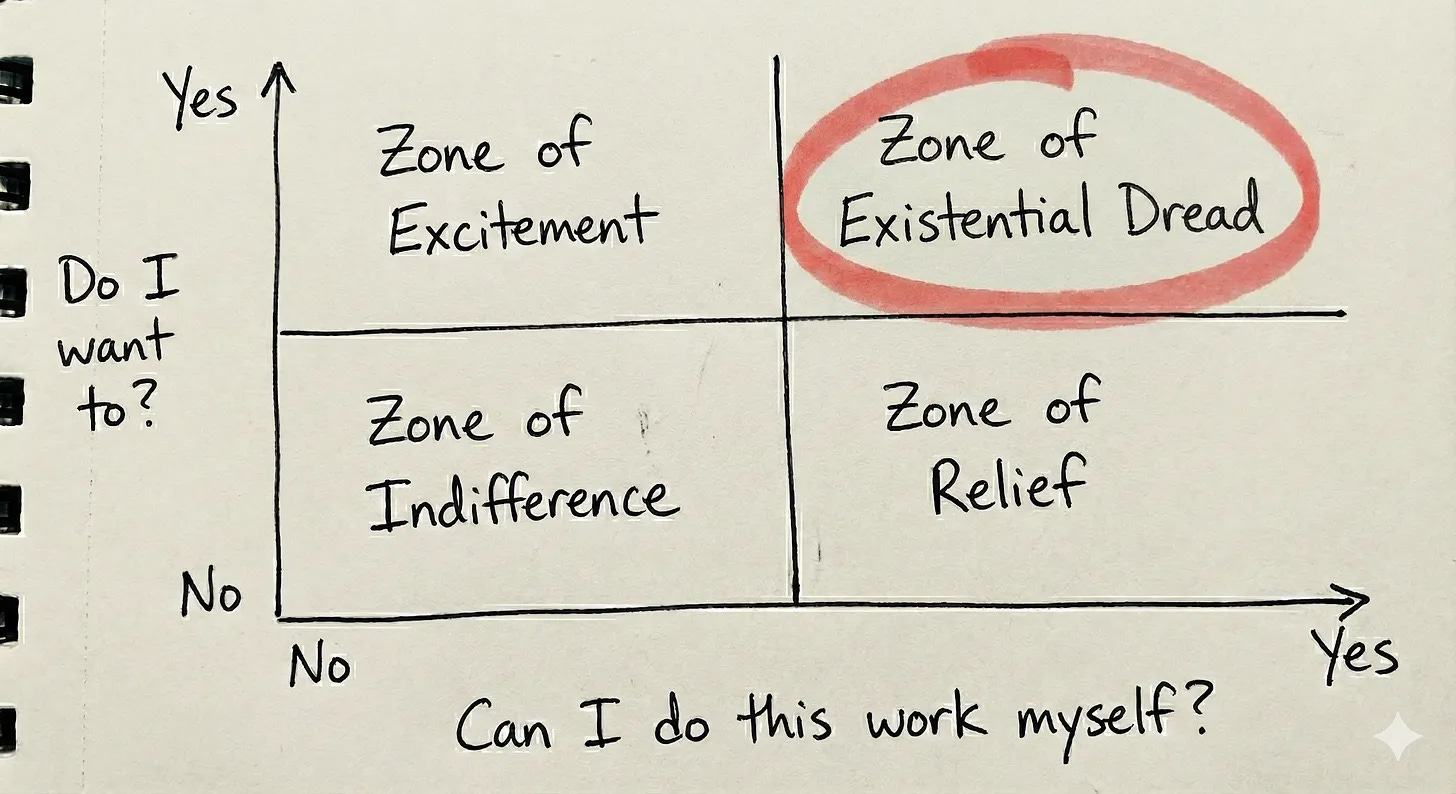

Here’s the matrix again, for reference:

After a lot of conversations, I’ve come to believe there are two viable paths through this framework—and one anti-pattern that founders should avoid at all costs.

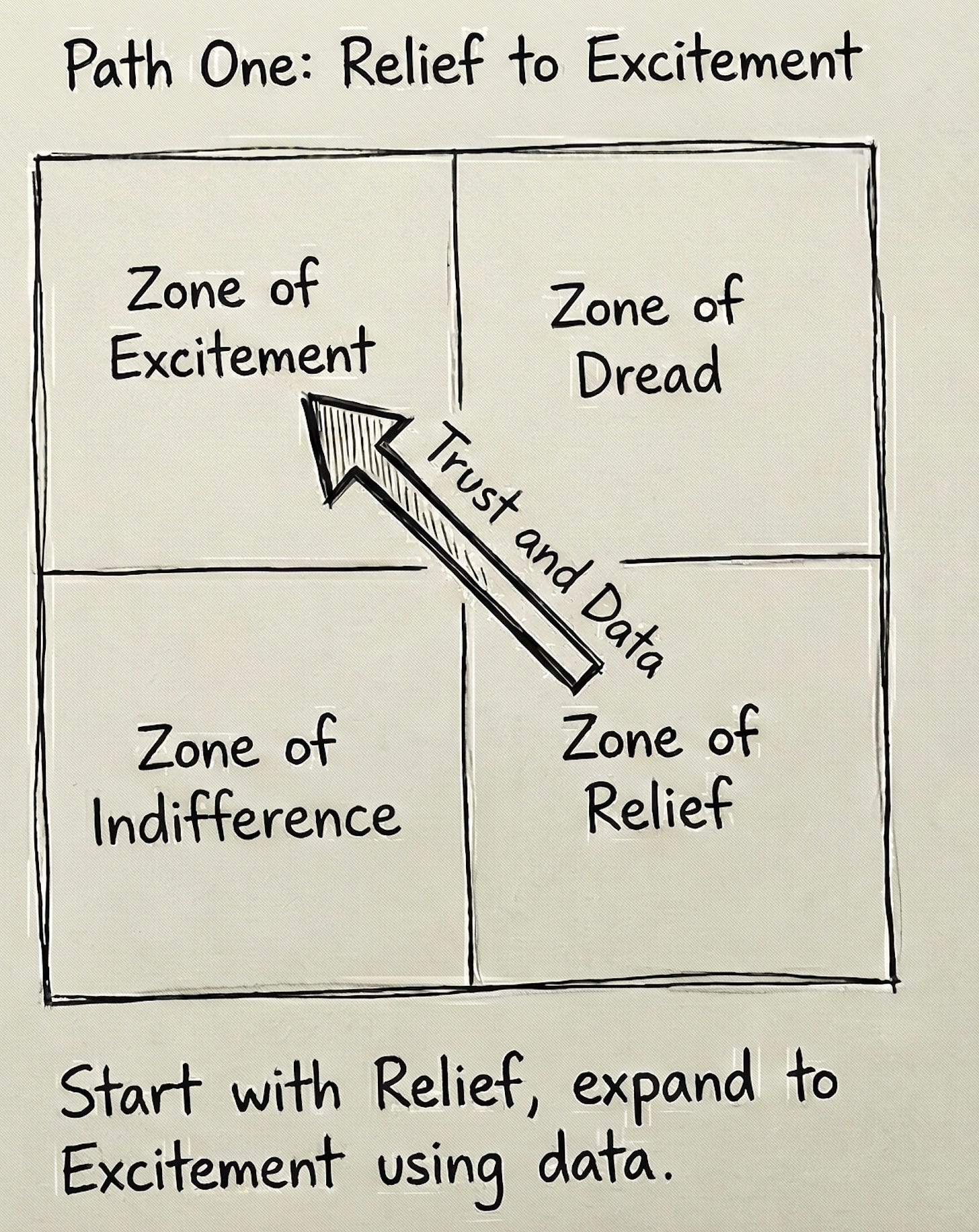

Path One: Relief to Excitement

The first path—and probably the more accessible one for most early-stage startups—is to start in the Zone of Relief and expand into the Zone of Excitement.

The Zone of Relief is where you’re solving a problem that people are capable of handling themselves, but really don’t want to. It’s work that doesn’t engage anyone’s uniquely human capacities. Nobody became a math teacher because they dreamed of spending their evenings marking worksheets. Nobody became a venture capitalist to play calendar Tetris.

Relief products have a few advantages as a wedge. They solve a real pain point that people will pay to eliminate. They integrate into existing workflows. They build trust through consistent, reliable execution of unglamorous tasks. And critically, they generate data.

That data is the bridge to the Zone of Excitement.

Consider an AI grading product for math teachers. The wedge is obvious: teachers can grade papers, but they’d rather not spend their evenings doing it. A product that handles this reliably creates immediate value.

But here’s where it gets interesting. Every graded assignment produces data—not just about what grade a student earned, but about what specific concepts they’re struggling with, what types of errors they make, and how their understanding is evolving over time.

A teacher couldn’t practically use this information to create individualized follow-up assignments for each student. There are only so many hours in the day. But an AI product can. It can take the output of grading and generate personalized homework that’s specifically designed to address each student’s gaps.

This is a Zone of Excitement expansion. Teachers want to provide personalized instruction—it’s closer to why many of them entered the profession in the first place—but they can’t do it at scale. The AI makes it possible.

The strategic logic is powerful: you’ve used a Relief product to build distribution, engagement, and data, then parlayed that into an Excitement product that creates deeper value and stickier relationships. The grading gets you in the door; the personalization keeps you there.

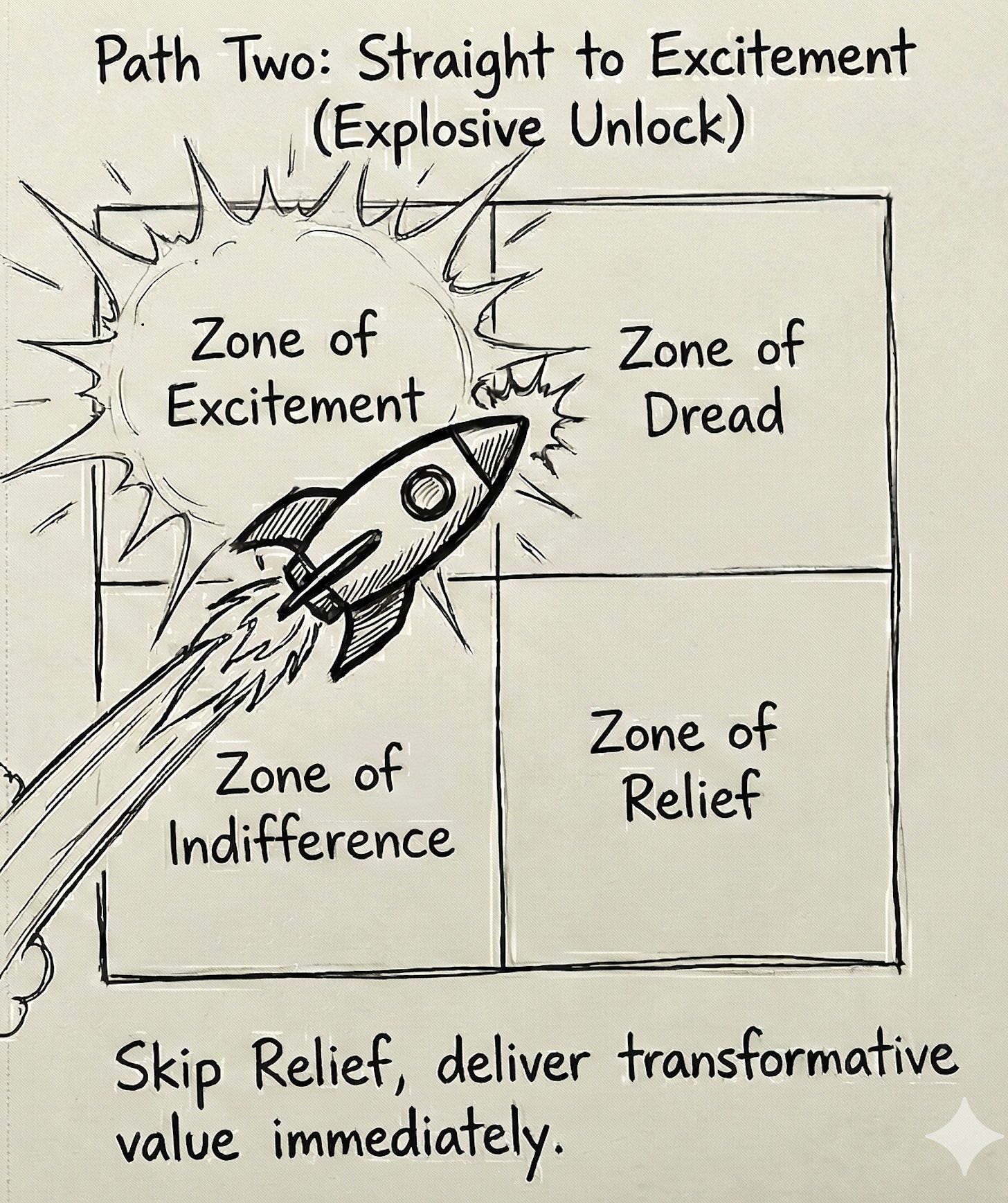

Path Two: Straight to Excitement

The second path is to skip Relief entirely and go straight for the Zone of Excitement. This is higher risk, but potentially faster and more explosive.

Suno is the clearest example. They didn’t start by handling some tedious adjacent task and expand from there. They just went straight to the thing: type a prompt, get a song. Something you wanted to do but couldn’t.

The numbers are staggering. Suno just raised $250 million at a $2.45 billion valuation. They’re generating $200 million in annual revenue. Users create 7 million songs per day—an entire Spotify catalog’s worth of music every two weeks.

Claude Code fits here too. It doesn’t handle the tedious parts of coding while I do the interesting bits. It unlocks work I simply couldn’t do before. The distance between “I wonder if I could build a tool that does X” and “I have a working prototype” has collapsed from months to hours.

The challenge with this path is that it’s harder to execute, and likely more capital intensive. You can’t start with a narrow use case and expand; you need to deliver something transformative from day one. The product has to be good enough that people immediately grasp what’s newly possible.

You also have fewer opportunities to build trust incrementally. With a Relief product, you can prove yourself on small stakes tasks before asking users to depend on you for bigger things. With an Excitement product, you’re asking for that trust upfront.

That said, when it works, it really works. Suno didn’t need to convince people that AI music generation was valuable—they just made it possible and people showed up in droves.

The Anti-Pattern: Dread as Provocation

There’s a third path that I’d advise founders to avoid entirely: using the Zone of Existential Dread as a deliberate provocation to get attention.

The canonical example is Cluely, the startup whose tagline at launch was literally “cheat on everything.” Their initial product was designed to help you cheat on interviews by feeding you answers in real-time—work that not only could you do yourself, but that specifically requires you to do it yourself for the whole exercise to have any meaning.

The Zone of Dread isn’t just about AI doing something you could do. It’s about AI doing something that violates fundamental social contracts. The entire point of a job interview is to create an accurate picture of a candidate’s capabilities. A product that short-circuits this isn’t just disrupting a workflow—it’s actively eroding trust in social institutions.

I’m not naive about the world. People cheat on interviews. Companies lie in job postings. The labor market is full of asymmetric information and principal-agent problems. But there’s a difference between acknowledging that reality and building a business that accelerates the erosion of whatever trust remains.

To their credit (or perhaps discredit), Cluely understood exactly what they were doing. The provocation was the point. Rage bait goes viral. A founder getting suspended from Columbia for using his own tool to fake interviews is a story people share. Within weeks of launch, they had 70,000 signups and $5.3 million in seed funding. A few months later, Andreessen Horowitz led a $15 million Series A.

Here’s the problem: they had “rage market fit,” not product-market fit.

Rage market fit is when people engage with your product because it makes them angry or fascinated by its audacity, not because it genuinely solves their problems. It’s a sugar high that feels like growth but doesn’t convert to lasting value.

The trajectory tells the story. After the initial virality faded and retention proved elusive, Cluely has tried to pivot toward something resembling a Zone of Relief product—an AI meeting assistant, a note-taker. But they’re doing it from a position of weakness. They’ve already told the world exactly who they are.

The deeper issue is trust. Zone of Relief products work precisely because users trust them to handle important-but-tedious tasks reliably. You earn that trust through consistent, unglamorous execution. You don’t earn it by announcing to the world that your company exists to help people deceive each other.

Implications for Founders and Investors

If you’re building an AI company, I’d encourage you to think carefully about where you’re starting and where you’re trying to go.

If you’re pursuing Path One (Relief → Excitement):

Pick a wedge that’s genuinely painful and ubiquitous in your target market

Design for data collection from day one—think about what information your Relief product will generate that could power an Excitement expansion

Build trust through reliable execution before attempting the expansion

Make sure the Excitement product is genuinely something users want to do but couldn’t, not just a feature addition

If you’re pursuing Path Two (Straight to Excitement):

Be honest with yourself about whether you’re actually enabling something new or just making an existing task slightly easier

Plan for the trust-building challenge—you don’t have the luxury of proving yourself on low-stakes tasks first

Be prepared for a longer, harder road to initial traction

Make sure the magic is immediately apparent

If you’re tempted by the anti-pattern:

Don’t.

Seriously, don’t.

The attention is intoxicating but the business fundamentals are terrible

You’re optimizing for a viral moment, not a company

From an investor’s perspective, I’ve become increasingly focused on the path from wedge to expansion. A Relief product that has no obvious route to Excitement is probably a feature, not a company. An Excitement product that can’t articulate why it’s genuinely enabling something new is probably riding a hype cycle.

And anything that starts in the Zone of Dread? That’s a pass. Life’s too short to invest in companies that make the world worse.

The robots are coming regardless. The question is whether we build them to extend human capability or to undermine human trust. I know which side I’m on.