How I stopped worrying and learned to love the brainrot

Building for fragmented attention in the age of AI.

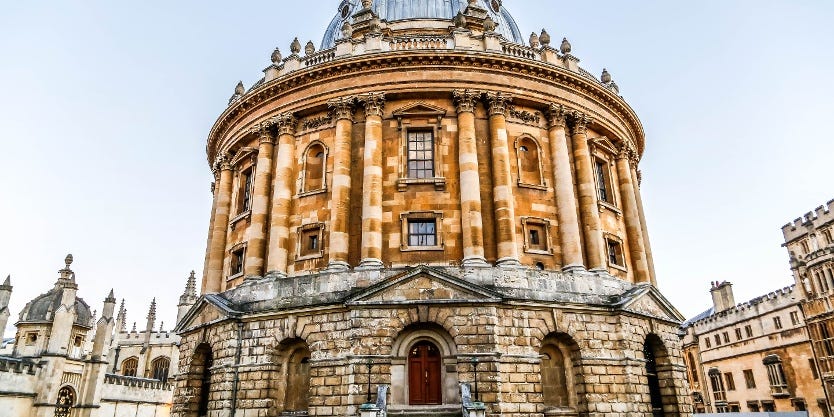

I spent much of my college years in the Radcliffe Camera, surrounded by leather-bound tomes and motes of dust dancing in centuries-old light. No wifi, no smartphones, no feeds. Just long stretches of more or less uninterrupted focus and the occasional creak of ancient wooden chairs.

That world is gone. As an Xennial—analog childhood, digital adulthood—I've watched our attention spans and—let’s be honest—my own fragment in real time.

These days, I catch myself doomscrolling Twitter while watching YouTube videos and responding to Slack messages. I'm not sure if this is evolution or decay. Maybe it's both.

What I am sure of is that fighting it is futile. When people talk about "fixing" modern attention spans, they sound like Renaissance scholars lamenting the printing press. They're not wrong about what we're losing.

Multitasking is a myth - research tells us it’s really just rapid task switching and it mostly just stresses us out and makes us dumber.

So, what happens next?

The science of attention suggests that perhaps all hope is not lost. In 1984, before we all carried dopamine slot machines in our pockets, psychologist Christopher Wickens proposed that our brains aren't single processors—they're parallel systems. Visual processing happens in one channel, auditory in another. We've always been capable of handling multiple streams of information. We just haven't had tools built for it.

Consider Memenome, which converts academic papers into TikTok-style brainrot videos with gameplay footage and AI narration. Your first reaction might be horror—mine was. But something interesting is happening here beyond just surrender to shortened attention spans.

Is this essay too long? This talking fish will give you the gist in under 60 seconds.

What's changed isn't just our attention—it's our ability to work with it. Generative AI makes it possible to transform content automatically, to personalize it, to make it flow through these dual channels without armies of video editors and voice actors.

Now we can turn PDFs into podcasts, into talking fish, into video games.

This isn't without cost. Something is lost when we optimize everything for rapid consumption. Deep focus isn't just about information processing—it's about giving ideas room to breathe, about following unexpected connections, about the kind of thinking that happens in the spaces between thoughts.

But the opportunities are too big to ignore. The same principles that make memenome work could reshape technical documentation, corporate training, product manuals—anywhere knowledge needs to move efficiently. The future won't look like a quieter version of the past. It'll look different, and that's okay.

The question is how we build tools that work with these new patterns while preserving what matters about learning and thinking.

If you are building in this area, we’d like to talk to you.

Love the title!