AI Needs Game Designers

What StarCraft and Factorio teach us about the future of work.

Last month, I wrote about how my workday has changed:

The new rhythm of my workday goes something like this: set Claude Code working on a feature spec, flip to a founder call, come back and review what it’s done, give it notes and set it writing tests, jump to an LP call, return to find the tests ready for review. Rinse, repeat. Meanwhile, Boardy is pinging my inbox and my WhatsApp with founder intros—some good ones, annoyingly—and Howie (an F4 Fund portfolio company) has quietly scheduled three meetings while I wasn’t looking.

It’s a different cadence than I’m used to. More context-switching, more plates spinning, more checking in on work that’s been happening while I was elsewhere. It demands a kind of multiplexed attention that would have felt scattered a year ago. Now it just feels like the job. And somehow, despite the constant juggling, I get a lot more done.

This is just... my life now? I don’t remember signing up for it. One day I was a normal person who used software; now I’m in what feels like a series of ongoing relationships with entities that remember things about me, have opinions, and occasionally make small talk.

I'm not a developer. But the pattern I'm describing—interleaving human attention with autonomous AI work—is becoming universal. And the most advanced version of it, the bleeding edge where people are figuring out what this all means, is happening in software development right now.

The orchestration era

On New Year’s Day, Steve Yegge dropped Gas Town: a framework for running 20-30 Claude Code instances simultaneously. Yegge describes it as “an industrialized coding factory manned by superintelligent chimpanzees” that “can wreck your shit in an instant” if you’re not an experienced chimp-wrangler.

Gas Town casts you, feckless human, as The Overseer in charge of an army of agents with seven distinct roles like The Mayor (your concierge and chief-of-staff) Polecats (ephemeral workers that swarm tasks), Refinery (manages the merge queue), and Witness (watches over polecats and unsticks them when they drift). Work flows through “convoys” that start, execute, and land without intervention.

What matters isn't speed—it's that the system keeps running without you. “Gas Town can work all night,” Yegge writes, “if you feed it enough work.” You design features, file implementation plans, sling work to your agents, then check back later. The system keeps running.

This pattern is going to go broader than software development. I think 2026 will be the year of Claude Code, and Nikunj Kothari adeptly frames the reason why: “Claude Code should be thought of as Claude Computer. Alien intelligence that has human tools—browser, filesystem, terminal commands—with generalized ability to do ANY task. Terminal UX is all that’s stopping folks from utilizing this all the time.”

When better interfaces arrive, orchestration will go mainstream: spinning up agents, directing their work, monitoring progress, intervening when they drift, reintegrating outputs. Parallel attention across autonomous systems.

What gamers already know

This skill set already exists. It’s been honed for decades by people who play certain kinds of video games.

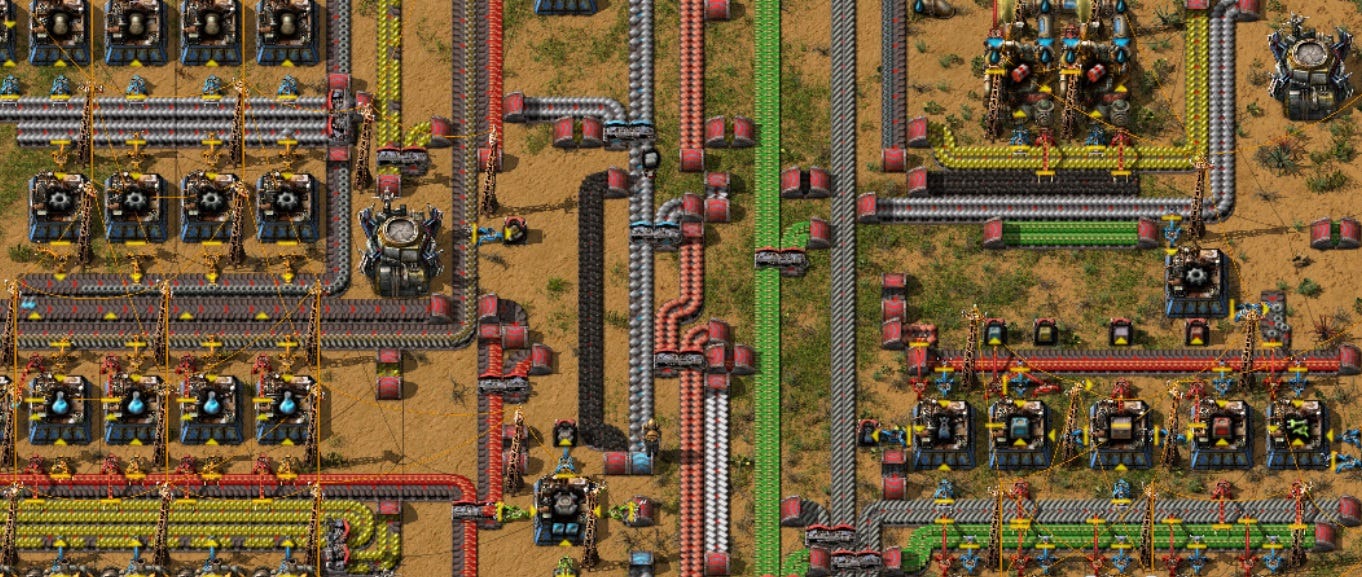

Last year, the Financial Times published a piece about Factorio’s grip on Silicon Valley (subscription gated - here’s a snarkier but worse PC Gamer article about it).

Shopify CEO Tobi Lütke lets employees expense their copies. “Factorio is the one video game that everyone at Shopify can expense,” he told the Invest Like The Best podcast, “because it’s just bound to be good for Shopify if people play Factorio for a little while. We are building global supply chains, and Factorio makes a game out of that kind of thinking.”

But the better analogy for agent orchestration might be StarCraft. Lütke shouted it out in the same interview as “a good teaching tool for tech workers.”

In real-time strategy games, you’re constantly managing multiple simultaneous processes: building your economy, training units, scouting enemy positions, micromanaging battles, researching upgrades. Pro players maintain 300+ actions per minute, but raw speed isn’t the point. The skill is attention allocation—knowing when to check on your expansion, when to shift focus to your army, when a fight needs intervention versus when you trust your units to handle it.

This maps almost directly to multi-agent work:

Parallel attention management. RTS players maintain awareness of multiple processes while focusing on the most critical. You’re monitoring everything but selectively intervening. That’s exactly what you do when running several Claude instances—or, in Yegge’s telling, when you’re the Overseer managing Polecats, Crew, and the Refinery.

Systems that run without you. Factorio factories and StarCraft economies keep producing while you attend to other things. Gas Town convoys “start up, complete, and land without intervention.” The design goal is the same: build something that works autonomously, then check back.

Context-switching as the game. In deep work, context-switching is a productivity killer. In RTS, it is the game. Rapid shifts between micro and macro, offense and defense, multiple fronts—this is the rhythm of agent orchestration.

The UX gap

Gas Town works, but it’s built on tmux. Yegge is upfront about this: “You will have to learn a bit of tmux. Or, you can wait until someone writes a better UI for Gas Town.”

This is terrible UX for a novel interaction paradigm. Managing autonomous agents through terminal commands is like playing StarCraft by typing coordinates.

Game designers have spent decades solving exactly this problem: how do you let humans direct complex, multi-agent systems in real-time? How do you surface the right information at the right moment? How do you make something intricate feel intuitive?

The command interfaces in RTS games—control groups, minimaps, production queues, alert systems—are the result of thirty years of iteration on parallel attention management. StarCraft 2’s UI is one of the most refined solutions to human-agent coordination that exists.

Someone is going to build the StarCraft UI for AI agents. An interface where you spin up workers, assign them to control groups, see their status on a dashboard, get alerts when they need attention, coordinate their work through something better than a shared markdown file.

The people most likely to build it well are game designers.

What this means

If you’re building AI tooling: the talent pool you need might not be where you’re looking. Game designers and RTS veterans understand parallel attention, autonomous systems, and interfaces that make complexity legible. They’ve been training for this.

If you’re a founder in this space, consider that games are more than entertainment - they’re decades of UX R&D on exactly the problems AI orchestration needs to solve.

The discourse about whether games need AI is backwards. AI needs what game designers know.

I once had a friend coach me while playing Startcraft 2. He basically stood behind me and kept repeating “make more probes” while I played. That was 10x higher impact that anything else he could have taught me… at any moment I should be making more probes, since that means I’d mine more minerals/gas and could produce more of everything without getting resource constrained.

Is there anything semi-obvious but easy to forget that someone standing behind you should just keep reminding you to do?

Yes!! Yes yes yes yes! This article is the article I wished I'd written.

I’ve been thinking about this over the past year, and the best description I’ve had for this mindset is “systems thinking”. It’s the ability to work with interconnected componentized systems, swap out the pieces, and manage the whole.

In Starcraft, the components are units, buildings, and economy. In modern software delivery, it’s containers and pods and Kubernetes. And now we’re migrating to agent orchestrators and Gas Town.

And… humans have been thinking about this for a LONG time. The industrialists of yore built their empires on similar systems thinking (only with real humans instead of simulated AI humans). I bet there will be a lot to learn from early 20th century empire-builders.